Plot summary

Eliza escapes with her son, Tom sold "down the river"

The book opens with a Kentucky farmer named Arthur Shelby facing the loss of his farm because of debts. Even though he and his wife, Emily Shelby, believe that they have a benevolent relationship with their slaves, Shelby decides to raise the needed funds by selling two of them — Uncle Tom, a middle-aged man with a wife and children, and Harry, the son of Emily Shelby’s maid Eliza — to a slave trader. Emily Shelby hates the idea of doing this because she had promised her maid that her child would never be sold; Emily's son, George Shelby, hates to see Tom go because he sees the man as his friend and mentor.

When Eliza overhears Mr. and Mrs. Shelby discussing plans to sell Tom and Harry, Eliza determines to run away with her son. The novel states that Eliza made this decision because she fears losing her only surviving child (she had already miscarried two children). Eliza departs that night, leaving a note of apology to her mistress.

While all of this is happening, Uncle Tom is sold and placed on a riverboat, which sets sail down the Mississippi River. While on board, Tom meets and befriends a young white girl named Eva. When Eva falls into the river, Tom saves her. In gratitude, Eva's father, Augustine St. Clare, buys Tom from the slave trader and takes him with the family to their home in New Orleans. During this time, Tom and Eva begin to relate to one another because of the deep Christian faith they both share.

Eliza's family hunted, Tom's life with St. Clare

During Eliza's escape, she meets up with her husband George Harris, who had run away previously. They decide to attempt to reach Canada. However, they are now being tracked by a slave hunter named Tom Loker. Eventually Loker and his men trap Eliza and her family, causing George to shoot Loker. Worried that Loker may die, Eliza convinces George to bring the slave hunter to a nearby Quaker settlement for medical treatment.

Back in New Orleans, St. Clare debates slavery with his Northern cousin Ophelia who, while opposing slavery, is prejudiced against black people. St. Clare, however, believes he is not biased, even though he is a slave owner. In an attempt to show Ophelia that her views on blacks are wrong, St. Clare purchases Topsy, a young black slave. St. Clare then asks Ophelia to educate her.

After Tom has lived with the St. Clares for two years, Eva grows very ill. Before she dies she experiences a vision of heaven, which she shares with the people around her. As a result of her death and vision, the other characters resolve to change their lives, with Ophelia promising to throw off her personal prejudices against blacks, Topsy saying she will better herself, and St. Clare pledging to free Uncle Tom.

Tom sold to Simon Legree

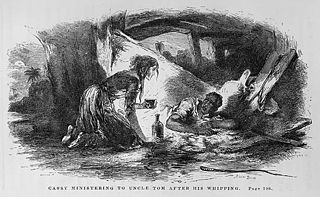

Before St. Clare can follow through on his pledge, however, he dies after being stabbed while entering a New Orleans tavern. His wife reneges on her late husband's vow and sells Tom at auction to a vicious plantation owner named Simon Legree. Legree (a transplanted northerner) takes Tom to rural Louisiana, where Tom meets Legree's other slaves, including Emmeline (whom Legree purchased at the same time). Legree begins to hate Tom when Tom refuses Legree's order to whip his fellow slave. Legree beats Tom viciously, and resolves to crush his new slave's faith in God. Despite Legree's cruelty, however, Tom refuses to stop reading his Bible and comforting the other slaves as best he can. While at the plantation, Tom meets Cassy, another of Legree's slaves. Cassy was previously separated from her son and daughter when they were sold; unable to endure the pain of seeing another child sold, she killed her third child.

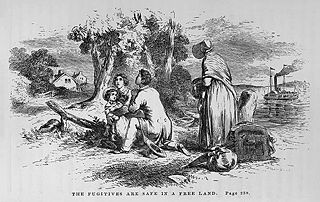

At this point Tom Loker returns to the story. Loker has changed as the result of being healed by the Quakers. George, Eliza, and Harry have also obtained their freedom after crossing into Canada. In Louisiana, Uncle Tom almost succumbs to hopelessness, as his faith in God is tested by the hardships of the plantation. However, he has two visions, one of Jesus and one of Eva, which renew his resolve to remain a faithful Christian, even unto death. He encourages Cassy to escape, which she does, taking Emmeline with her. When Tom refuses to tell Legree where Cassy and Emmeline have gone, Legree orders his overseers to kill Tom. As Tom is dying, he forgives the overseers who savagely beat him. Humbled by the character of the man they have killed, both men become Christians. Very shortly before Tom's death, George Shelby (Arthur Shelby's son) arrives to buy Tom’s freedom, but finds he is too late.

Final section

On their boat ride to freedom, Cassy and Emmeline meet George Harris' sister and accompany her to Canada. Once there, Cassy discovers that Eliza is her long-lost daughter who was sold as a child. Now that their family is together again, they travel to France and eventually Liberia, the African nation created for former American slaves. There they meet Cassy's long-lost son. George Shelby returns to the Kentucky farm and frees all his slaves. George tells them to remember Tom's sacrifice and his belief in the true meaning of Christianity.

Major characters in Uncle Tom's Cabin

Uncle Tom

Uncle Tom, the title character, was initially seen as a noble, long-suffering Christian slave. In more recent years, however, his name has become an epithet directed towards African-Americans who are accused of selling out to whites (for more on this, see the creation and popularization of stereotypes section). Stowe intended Tom to be a "noble hero"[20] and praiseworthy person. Throughout the book, far from allowing himself to be exploited, Tom stands up for his beliefs and is grudgingly admired even by his enemies.

Eliza

A slave (personal maid to Mrs. Shelby), she escapes to the North with her five-year old son Harry after he is sold to Mr. Haley. Her husband, George, eventually finds Eliza and Harry in Ohio, and emigrates with them to Canada, then France and finally Liberia.

The character Eliza was inspired by an account given at Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati by John Rankin to Stowe's husband Calvin, a professor at the school. According to Rankin, in February, 1838 a young slave woman had escaped across the frozen Ohio River to the town of Ripley with her child in her arms and stayed at his house on her way further north.[21]

Eva

Eva, whose real name is Evangeline St. Clare, is the daughter of Augustine St. Clare. Eva enters the narrative when Uncle Tom is traveling via steamship to New Orleans to be sold, and he rescues the 5 or 6 year-old girl from drowning. Eva begs her father to buy Tom, and he becomes the head coachman at the St. Clare plantation. He spends most of his time with the angelic Eva, however.

Eva constantly talks about love and forgiveness, even convincing the dour slave girl Topsy that she deserves love. She even touches the heart of her sour aunt, Ophelia.

Eventually Eva falls terminally ill. Before dying, she gives a lock of her hair to each of the slaves, telling them that they must become Christians so that they may see each other in Heaven. On her deathbed, she convinces her father to free Tom, but because of circumstances the promise never materializes.

A similar character, also named Little Eva, later appeared in the children's novel Little Eva: The Flower of the South by Philip J. Cozans (although this ironically was an anti-Tom novel). To a certain degree, the Little Eva portrayed by Cozans could be the same Eva introduced by Stowe.

Simon Legree

A cruel slave owner — a Northerner by birth — whose name has become synonymous with greed. His goal is to demoralize Tom and break him of his religious faith; he eventually beats Tom to death out of frustration for his slave's unbreakable belief in God. The novel reveals that, as a young man, he had abandoned his sickly mother for a life at sea, and ignored her letter to see her one last time at her deathbed. He sexually exploits Cassie, who despises him, and later sets his designs on Emmaline.

Topsy

A "ragamuffin" young slave girl. When asked if she knows who made her, she professes ignorance of both God and a mother, saying "I s'pect I growed. Don't think nobody never made me." She is transformed by Little Eva's love. During the early-to-mid 1900s, several doll manufacturers created Topsy and Topsy-type dolls.

The phrase "growed like Topsy" (later "grew like Topsy"; now somewhat archaic) passed into the English language, originally with the specific meaning of unplanned growth, later sometimes just meaning enormous growth.[22]

Other characters

There are a number of secondary and minor characters in Uncle Tom's Cabin. Among the more notable are:

- Arthur Shelby, Tom's master in Kentucky. Shelby is characterized as a "kind" slaveowner and a stereotypical Southern gentleman.

- Emily Shelby, Arthur Shelby's wife. A deeply religious woman who strives to be a kind and moral influence upon her slaves. She is appalled when her husband sells his slaves with a slave trader. As a woman, she has no legal way to stop this, as all property belongs to her husband.

- George Shelby, Arthur and Emily's son, who sees Tom as a "friend" and as the perfect Christian.

- Augustine St. Clare, Tom's second owner and father of Eva. Of the slaveowners in the novel, the most sympathetic character. St. Clare is complex, often sarcastic, with a ready wit. After a rocky courtship he marries a woman he grows to hold in contempt, though he is too polite to let it show. St. Clare recognizes the evil in chattel slavery, but is not willing to relinquish the wealth it brings him. After his daughter's death he becomes more sincere in his religious thoughts, and starts to read the Bible to Tom. He plans on finally taking action against slavery by freeing his slaves, but his good intentions ultimately come to nothing.

Major themes

Uncle Tom's Cabin is dominated by a single theme: the evil and immorality of slavery.[23] While Stowe weaves other subthemes throughout her text, such as the moral authority of motherhood and the redeeming possibilities offered by Christianity,[3] she emphasizes the connections between these and the horrors of slavery. Stowe pushed home her theme of the immorality of slavery on almost every page of the novel, sometimes even changing the story's voice so she could give a "homily" on the destructive nature of slavery[24] (such as when a white woman on the steamboat carrying Tom further south states, "The most dreadful part of slavery, to my mind, is its outrages of feelings and affections—the separating of families, for example.").[25] One way Stowe showed the evil of slavery[18] was how this "peculiar institution" forcibly separated families from each other.[26]

Because Stowe saw motherhood as the "ethical and structural model for all of American life,"[27] and also believed that only women had the moral authority to save[28] the United States from the demon of slavery, another major theme of Uncle Tom's Cabin is the moral power and sanctity of women. Through characters like Eliza, who escapes from slavery to save her young son (and eventually reunites her entire family), or Little Eva, who is seen as the "ideal Christian",[29] Stowe shows how she believed women could save those around them from even the worst injustices. While later critics have noted that Stowe's female characters are often domestic clichés instead of realistic women,[30] Stowe's novel "reaffirmed the importance of women's influence" and helped pave the way for the women's rights movement in the following decades.[31]

Stowe's puritanical religious beliefs show up in the novel's final, over-arching theme, which is the exploration of the nature of Christianity[3] and how she feels Christian theology is fundamentally incompatible with slavery.[32] This theme is most evident when Tom urges St. Clare to "look away to Jesus" after the death of St. Clare's beloved daughter Eva. After Tom dies, George Shelby eulogizes Tom by saying, "What a thing it is to be a Christian."[33] Because Christian themes play such a large role in Uncle Tom's Cabin—and because of Stowe's frequent use of direct authorial interjections on religion and faith—the novel often takes the "form of a sermon."[34]

Style

Uncle Tom's Cabin is written in the sentimental[35] and melodramatic style common to 19th century sentimental novels[5] and domestic fiction (also called women's fiction). These genres were the most popular novels of Stowe's time and tended to feature female main characters and a writing style which evoked a reader's sympathy and emotion.[36] Even though Stowe's novel differs from other sentimental novels by focusing on a large theme like slavery and by having a man as the main character, she still set out to elicit certain strong feelings from her readers (such as making them cry at the death of Little Eva).[37] The power in this type of writing can be seen in the reaction of contemporary readers. Georgiana May, a friend of Stowe's, wrote a letter to the author stating that "I was up last night long after one o'clock, reading and finishing Uncle Tom's Cabin. I could not leave it any more than I could have left a dying child."[38] Another reader is described as obsessing on the book at all hours and having considered renaming her daughter Eva.[39] Evidently the death of Little Eva affected a lot of people at that time, because in 1852 alone 300 baby girls in Boston were given that name.[39]

Despite this positive reaction from readers, for decades literary critics dismissed the style found in Uncle Tom's Cabin and other sentimental novels because these books were written by women and so prominently featured "women's sloppy emotions."[40] One literary critic said that had the novel not been about slavery, "it would be just another sentimental novel,"[41] while another described the book as "primarily a derivative piece of hack work."[42] Incalled Uncle Tom's Cabin "Sunday-school fiction" and full of "broadly conceived melodrama, humor, and pathos."[43]

However, in 1985 Jane Tompkins changed this view of Uncle Tom's Cabin with her book In Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction.[40] Tompkins praised the style so many other critics had dismissed, writing that sentimental novels showed how women's emotions had the power to change the world for the better. She also said that the popular domestic novels of the 19th century, including Uncle Tom's Cabin, were remarkable for their "intellectual complexity, ambition, and resourcefulness"; and that Uncle Tom's Cabin offers a "critique of American society far more devastating than any delivered by better-known critics such as Hawthorne and Melville."[43]

Reactions to the novel

Uncle Tom's Cabin has exerted an influence "equaled by few other novels in history."[44] Upon publication, Uncle Tom's Cabin ignited a firestorm of protest from defenders of slavery (who created a number of books in response to the novel) while the book elicited praise from abolitionists. As a best-seller, the novel heavily influenced later protest literature (such as The Jungle by Upton Sinclair).

--http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncle_Tom's_Cabin

No comments:

Post a Comment